Prevention or Punishment: Nurses cope with workplace violence as Congress debates solutions

A federal push to protect healthcare workers is stalled by a deep divide over whether to focus on prevention through staffing or punishment through tougher laws.

(InvestigateTV) — From being punched and kicked to being stabbed, healthcare workers across the country often face a reality that was never part of their training.

The problem has become so severe that it has finally captured the attention of Congress.

However, as lawmakers in Washington debate a solution, a deep and bitter divide has emerged between the very groups trying to protect these essential workers, leaving nurses caught in the middle of a fight over how to keep them safe.

The 911 calls paint a picture of absolute chaos, a scene of terror unfolding not on a dark street corner, but in the sterile, brightly-lit hallways of a Florida hospital.

“There’s some guy in here that’s nuts,” a caller pleads.

“He stabbed a nurse?” a dispatcher asks in disbelief. “Yes,” the voice on the other end confirms.

“Did he hurt somebody with the scissors?” “Yes, he did.”

The calls, one after another, build a horrifying narrative. A patient, brought in for mental health reasons, had launched a brutal attack.

The pleas for help from inside the hospital grew more desperate.

“You said they assaulted the employee until they passed out?” “Yeah, unconscious.”

“This could be nearly a fatality,” another caller warns. “This employee may not make it.”

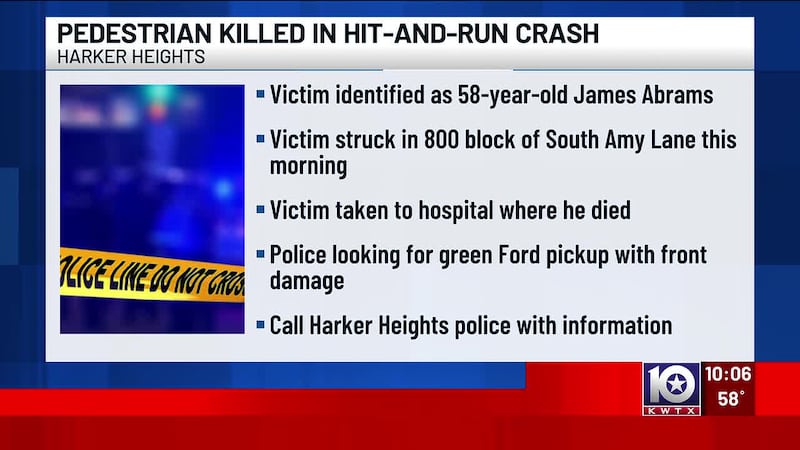

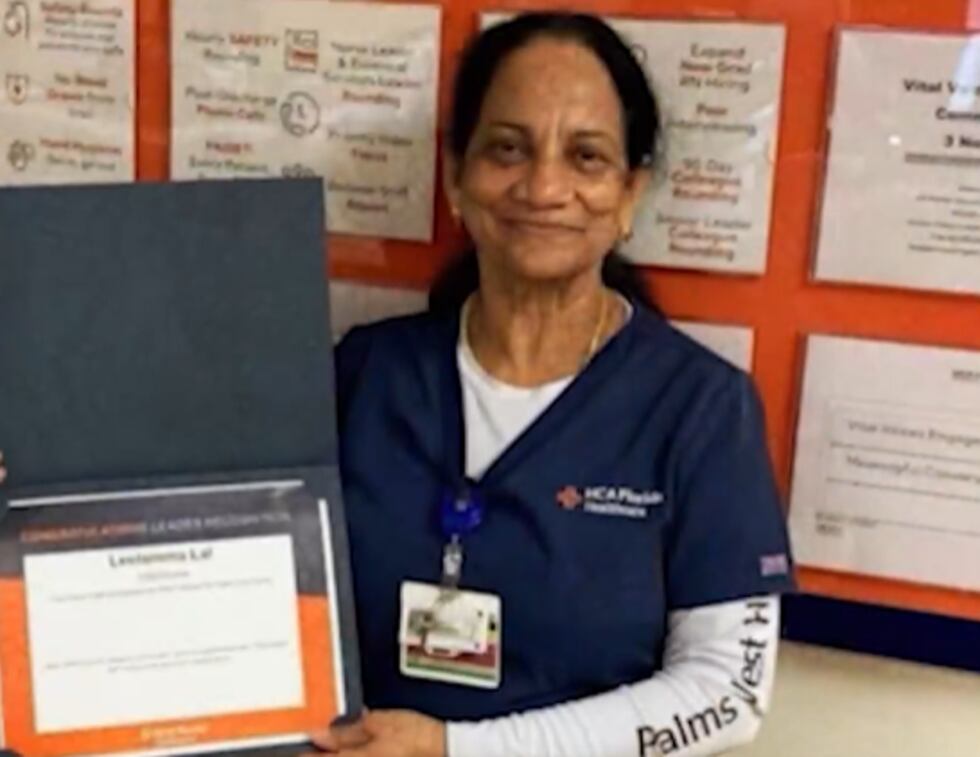

That employee was Leelamma Lal, a nurse who, in less than a minute, went from caring for patients to becoming one herself. The attack was so severe that months later, she was still too injured to speak about it. Her attorney, Karen Terry, described the aftermath in stark terms.

“Almost beaten to death,” Terry said. “She has suffered extensive injuries, massive injuries to her face.”

The attack on Lal was not a freak accident or an isolated incident. It was a brutal example of a violent epidemic surging through America’s healthcare system, with nurses on the front lines bearing the brunt of the assaults.

According to a recent survey by National Nurses United (NNU), the nation’s largest union of registered nurses, the crisis is escalating. More than 80 percent of nurses surveyed reported experiencing some form of workplace violence, ranging from verbal threats to physical attacks. Nearly half said the violence has gotten worse in recent years.

A Job Hazard No One Signed Up For

In a quiet room in Kansas City, Missouri, three nurses shared stories that have become disturbingly common. For them, handling violence is no longer a rare emergency. Instead, it’s becoming part of the job.

“She was able to grab me by the back of the head,” recalled nurse Lee Barker. “She hit me in the back of the head a couple of times.”

When asked how often they witness or experience violence, Linnea Edlin, another nurse, gave a chillingly routine answer.

“Between weapons coming in, between people getting hurt or almost getting hurt, it’s often,” she said.

This constant threat is a reality that was absent from their education.

When asked if the risk of violence was ever discussed in nursing school, the three nurses answered with a collective and unequivocal “No.”

“I do think that it’s something that nurses should be prepared for,” Barker said, reflecting a grim acceptance of the new normal.

Lucy Mendez, a nurse who went on strike over safety concerns in New Orleans, echoed the sentiment.

“I have gotten kicked, I’ve gotten punched before,” she said. “You get told some stories in nursing school, like you know to always be safe, know your surroundings, but I didn’t really expect that to be kind of an everyday thing that I have to worry about.”

This daily fear is the driving force behind the federal push for action. But the path forward is split in two, with two competing bills offering fundamentally different philosophies on how to solve the problem.

Prevention vs. Punishment

On one side is the Workplace Violence Prevention for Health Care and Social Service Workers Act.

Championed by nursing unions, this bill focuses on prevention. It would require healthcare employers nationwide to develop and implement a comprehensive, facility-specific plan to mitigate the risk of violence. At the heart of this approach, supporters say, is the issue of safe staffing.

“Safe staffing makes everyone safer, right?” said Jane Thomason, a lead industrial hygienist with NNU.

The union argues that chronic understaffing in hospitals is a primary driver of violence. When nurses are stretched thin, caring for too many patients at once, they cannot dedicate the time needed to recognize the warning signs of agitation and de-escalate a situation before it turns violent.

“If you don’t have time to be in your patient’s room and you’re rushing between patients, you’re not gonna be able to recognize those signs of escalation and intervene with that patient as early as if you were safely staffed,” Thomason explained.

The nurses in Kansas City described the direct impact of unsafe staffing ratios. Linnea Edlin recalled a shift where she was responsible for nine patients on an intensive psychiatric treatment unit.

“Is nine patients a lot?” she was asked. “Yes,” she replied firmly.

“The ratio that we advocate for, for federal legislation is 4:1.”

Lee Barker’s own attack underscores the danger.

“When I was getting attacked, we had one staff member show up,” Barker said.

Asked if better staffing could have prevented the assault, Barker’s answer was immediate.

“I absolutely think so. Safe staffing is the best way to prevent workplace violence.”

On the other side of the debate is the Safety from Violence for Healthcare Employees (SAVE) Act.

Supported by the American Hospital Association (AHA), this bill takes a punitive approach.

It seeks to toughen federal criminal penalties for individuals who knowingly assault healthcare workers, mirroring laws that protect airline and airport workers.

Claire Zangerle, the Chief Nurse Executive for the AHA, argues that mandated staffing ratios are not the answer.

“Mandated ratios are not going to solve the workplace violence issues,” she stated. “Because you add more nurses doesn’t mean the violence is going to abate.”

Instead, the AHA believes the threat of harsher punishment will act as a deterrent.

“What we want this law to do is we want this law to keep people from offending,” Zangerle said. She compared the proposed law’s effect to “having a police force in the hospital walking the beat, walking the units, so that there is that presence of those officers on those units, and that deters the crime.”

The Flaws in the Fixes

A number of nurses and their unions are opposed to the SAVE Act, arguing that it misdiagnoses the problem by treating sick patients as criminals.

“We don’t agree with it,” said Jake Liston, a nurse and union representative. “Our patients aren’t criminals.”

They point to a crucial fact: tougher penalties are not a new idea.

“At least 37 states already have enhanced criminal penalties on the books for workplace violence against healthcare workers,” said NNU’s Jane Thomason. “And many have had those in place for decades. And yet we’ve seen workplace violence rates continue to skyrocket.”

Maine, for instance, passed such a law in 2023. A year later, the data from Northern Light Health, a major healthcare system in the state, showed a negligible difference, with 799 recorded acts of violence in 2024 compared to 834 in 2022, before the law was passed.

Lisa Harvey McPherson, a government relations representative for the system, acknowledged the numbers weren’t lower but argued the law’s deterrent effect is hard to quantify.

“How many violent incidents didn’t occur because it’s tougher?” she mused. “That would be the unknown.”

Florida has a law on the books that enhances penalties for assaulting healthcare workers. That law was in effect the day Leelamma Lal was nearly beaten to death.

“It didn’t protect Miss Lal,” her attorney, Karen Terry, stated flatly.

The Mental Health Complication

A study conducted in Seattle with The Marshall Project found that 76% of healthcare assault cases involved people showing signs of serious mental illness.

This is the central fear for nurses like Linnea Edlin, who worry that the SAVE Act would disproportionately harm the most vulnerable patients.

“I think that is the scariest thing,” she said. “These are the patients that are the most likely to become violent, the patients that are in psychosis or are in mania… and that need the most hands-on attention, redirection and focus.”

This sentiment gets to the core of the nursing ethos.

“People come to the hospital because they’re sick,” said union rep Jake Liston. “And we need people to take care of them.” Criminalizing the symptoms of their illness, they argue, is not the answer.

Karen Terry believes the solution in Leelamma Lal’s case was not a law that would punish her attacker after the fact, but measures that would have prevented the attack in the first place.

“I think if they had had additional staff, I think if they had had trained armed security, this would not have happened,” she said.

In a statement provided to InvestigateTV, the hospital where Lal was attacked addressed the incident and its security protocols:

Although two different healthcare regulatory agencies recently concluded there were no deficiencies in [the hospital’s] protocols, hospital leadership has been developing security enhancements that have been, and will continue to be implemented in the coming days.

These additional measures include the contracting of a full-time deputy starting April 1 who will provide services beyond just an armed presence on our property. This resource will also provide education and training to colleagues and will be an integral part of the security team.

For security reasons, we will not provide specific details, but the plan is based on the recommendation from the Palm Beach County Sheriff’s office and Sheriff Bradshaw to ensure our efforts are in line with or exceed private security practices in Palm Beach County.

The Staffing Stalemate and the Front Lines Fight Back

The debate is further complicated by a fundamental disagreement about the state of the nursing profession itself. The American Hospital Association claims there is a critical nursing shortage, suggesting that even if safe staffing mandates were passed, there simply aren’t enough nurses to hire.

The nurses’ union fires back with a different narrative.

They argue there is no shortage of registered nurses, but rather a shortage of nurses willing to work in what they describe as unsafe and untenable conditions. They claim hundreds of thousands of qualified nurses are not actively working because the risks have become too high.

With the debate deadlocked in Washington, nurses are taking matters into their own hands.

In May of 2025, hundreds of nurses at University Medical Center in New Orleans, including Lucy Mendez, went on strike. Their key issue was workplace violence, and their central demand was for more staff to keep them safe.

Similar strikes over staffing and safety have erupted in Baltimore, Rochester, and Madison, signaling a growing unrest among a workforce that says it feels abandoned and unprotected.

While industry organizations and federal lawmakers remain divided, the nurses on the floor are left to prepare for a danger they never anticipated. They continue to show up for their shifts, caring for the sick and injured, all while they say they’re wrestling with the constant, nagging fear that they could be next. The pleas for help that echoed from that Florida hospital are now reverberating in union halls and on picket lines across the country, a desperate call for a solution to a crisis that can no longer be ignored.

Copyright 2025 Gray Media Group, Inc. All rights reserved.